Cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is the crux of a major humanitarian and environmental crisis that demands far greater attention from the wider world. Cobalt is a mineral used to power rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, which in turn power a striking majority of electronic devices worldwide, aiding in the transition away from fossil fuels. Congolese cobalt reserves are the most abundant in the world, and demand for the mineral continues to increase the more electric our world becomes.

Yet, predicated by a history of brutality, dehumanization, and overexploitation of Congolese people, the working conditions for cobalt mining in the Congo egregiously violate fair labor standards and environmental health. Right now, each of us has the power to help by taking action to uplift Congolese voices, advocate for Congolese rights, and spread awareness on the issue. Read on to learn more.

Content warning: mentions of sexual violence. Header image from the Washington Post.

Why Batteries Use Cobalt

Most rechargeable batteries you’ll find are lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries. These rechargeable batteries are used in personal electronics (cell phones, tablets, laptops, vapes, etc.), E-Bikes, electric toothbrushes, tools, hoverboards, scooters, and solar power backup storage. Electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (EVs and PHEVs) also typically contain a rechargeable Li-ion battery. Nearly every Li-ion battery contains cobalt, as it enhances their density and stability for safe and reliable use over longer periods of time.

Congolese cobalt reserves total around 4,000,000 metric tons, which amounts to about 48% of all existing cobalt globally. 73% of all cobalt produced in 2022 was mined in the DRC. EVs are the highest driver of cobalt demand, claiming 40% of cobalt produced in 2022. The demand for cobalt is projected to double from 189 kt (kilotons) in 2022 to around 388 kt by 2030, with 89% going toward powering EVs.

While cobalt is currently acting as an indispensable mineral to the transition toward clean energy, it is important to note that Li-ion batteries do not need cobalt to function. Alternative minerals, such as nickel, manganese, and iron, can also be used to power rechargeable batteries, though mining for these minerals can pose similar threats to mining for cobalt.

Tesla has reportedly been shifting toward cobalt-free batteries powered by lithium iron phosphate, with other auto and tech companies (such as Toyota, Hyundai, and Panasonic) beginning to follow suit. Additionally, MIT has recently announced a few of its researchers have developed a cobalt-free battery powered by organic materials. Given the questionable ethicality of mining cobalt alternatives, this could be a promising step forward.

Humanitarian and Environmental Violations in the Congo

Photo from MONUSCO/Sylvain Liechti. Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Mining operations in the Congo rely on outrageous levels of exploitation, unfair labor, and violence. Research done by the World Bank shows 62% of Congolese residents, around 60 million people, lived on less than $2.15 a day in 2022, which totals an average income per capita of around $500 each year. By contrast, the country’s annual GDP amounts to more than $55 billion—a discrepancy that illustrates an obscenely disproportionate distribution of wealth.

In mineral-rich cities such as Kolwezi, capital of the southern Lualaba province, mining has become so widespread that some operations have taken to demolishing civilian homes in order to expand their reach. Communities are not appropriately included in making these decisions, nor are they given ample warning for evacuation. Donat Kambola, president of the Initiative for Good Governance and Human Rights (IBGDH), has said, “People are being forcibly evicted, or threatened or intimidated into leaving their homes, or misled into consenting to derisory settlements. Often there was no grievance mechanism, accountability, or access to justice.”

Even worse, mining operations are a major source of sexual violence, particularly against women and children. Forty-eight women are raped every hour in the Congo, and those living close to mines are even more likely to experience non-partner sexual violence.

HATARI YA KUFA: RISK OF DYING (Swahili)

What’s more, mining cobalt is seriously dangerous. According to the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, cobalt is toxic to inhale and can cause asthma-like irritations or respiratory fits. Prolonged or repeated exposure can cause disabling or fatal lung scarring (fibrosis) that can often go unnoticed. It is an irritant to the eyes, nose, throat, and skin, and can spur an allergic reaction, itching, or rash upon dermal contact. It may also negatively impact the heart, liver, thyroid, and kidneys, and may even cause birth defects. The CDC even cites cobalt exposure as a potential cause for cancer.

This becomes all the more concerning when considering that hundreds of thousands of Congolese people, including young children, are handling and inhaling cobalt everyday, usually without basic protective equipment like gloves, face masks, or work clothes, according to a 2016 report by Amnesty International. It is estimated that around at least 2,000 people die from cobalt mining-related incidents each year.

These working conditions also intensify the spread of illness. The COVID-19 pandemic hit Congolese communities especially hard, exacerbated by other infectious diseases like cholera, measles, and Ebola. Many mines contain dirty water infested with bacteria. When miners enter such caves without protective equipment, they are immediately at risk of potentially fatal diseases like typhoid, cholera, and diarrhea.

Exploitation of minerals in the DRC is a source of significant environmental degradation as well. Toxic dumping pollutes the air and contaminates water, soil, and wildlife at the cost of failed crops, poisoned fish, and unsafe drinking water. “In this stream, the fish vanished long ago, killed by acids and waste from the mines,” says Lubumbashi resident Heritier Maloba of his childhood fishing hole. The air around mining operations is hazy, “full of grit, and toxic to breathe,” writes environmental scientist and sustainability consultant Charlotte Davey. Cobalt mining in the Congo releases greenhouse gasses too, with CO2 emissions reaching 9,260 tons in 2019.

History of Exploitation in the Congo

Slag heaps at a diamond mine in Bakwanga, Kasai, 1950.

All of these mining operations are predicated on a complex history of systemic exploitation of Congolese land and people. In an outstanding interview with political commentator Marc Lamont Hill, co-founder and executive director of the organization Friends of the Congo, Maurice Carney, details key events in the Congo’s history that have led to the crisis unfolding presently. (We highly recommend listening to the full interview for a more complete analysis of the topic.)

During the transatlantic slave trade, around 10 to 12 million Africans were trafficked to the Americas; of these, nearly half came from the Congo. Then came the scramble for Africa, in which European powers sought to colonize the entire continent for their own gain. The Congo was given to King Leopold of Belgium as his private property. He reigned over the Congo for 23 years, from 1885 to 1908, during which half the Congolese population was decimated for the sake of the king’s rubber and ivory extractions. An estimated 10 million Congolese people died to fuel Western industry.

International outcry forced the king to relinquish control of the Congo—but rather than turning the country over to its people, he passed it instead along to the Belgian state, which ruled the Congo as a “colonial outpost” from 1908 to 1960.

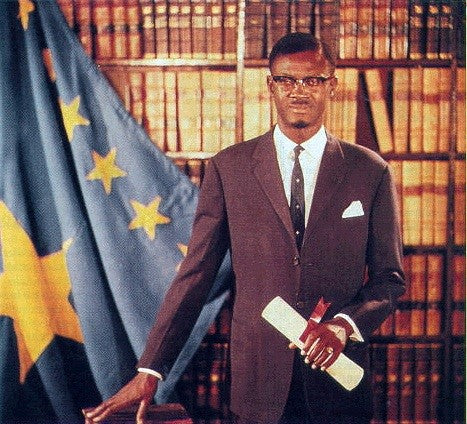

The Congo reached independence in 1960, with their first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, inaugurated on June 30, 1960. Yet Western powers, including the US and the UK, were already planning to overthrow him. Carney calls this the “largest covert action that the United States mounted in the 60s”—Lumumba was assassinated seven months later, on January 17, 1961.

Official portrait of Patrice Lumumba as prime minister in 1960.

Backed by US financial and military support, dictator Joseph Mobutu took power over the Congo for thirty years, beginning in 1965. By the end of the Cold War, Congolese people were organizing to re-establish a democratic governance. Rather than supporting this “burgeoning pro-democracy movement,” however, the US chose instead to back an invasion of the Congo by Rwanda and Uganda.

Thus began an astonishingly lethal eleven-year period of conflict and war. Between 1996 and 2007, an estimated 6 million Congolese people perished, with 5.4 million dying in the Second Congo War (1998-2003), which involved eleven countries. The UN dubbed it the deadliest conflict in the world since World War II.

As the UN brokered a peace agreement in 2002, they also conducted studies in which they identified 85 international companies they claimed violated laws related to natural resource extraction. They specifically named the US-backed leaders of Rwanda (Paul Kagame) and Uganda (Yoweri Museveni) as the “godfathers” of mineral exploitation in the Congo.

Since then, international mineral interest has increased such that China controls a majority of mines in the Congo today, processing 80% of cobalt in the world. In fact, around 2008 and 2009, China brokered a deal with the Congolese government to exchange $6 billion in minerals for infrastructure resources.

It is important to note that cobalt is not the only mineral mined in the Congo: The land is also rich with copper, gold, coltan, and diamonds. Carney says that “the Congo was designed by Europeans for plunder, for the extraction of minerals,” and that this design remains fundamentally unchanged today.

However, the Congo contains environmental resources that are “much more nourishing [than] what mining can yield,” writes storyteller Morgan Lynzi in a recent Instagram post, “yet the Congolese people have been denied the benefits of it.” In fact, a UN report concluded that the DRC has the potential to become an environmental powerhouse to the world, yet faces “alarming” threats surrounding deforestation, species depletion, heavy metal pollution, and land degradation from mining, “as well as an acute drinking water crisis which has left an estimated 51 million Congolese without access to potable water.” Another study found that the DRC has the potential to feed 2 billion people—yet, in 2021, nearly 22 million people faced starvation.

Depictions of the Congo in media also perpetuate the stereotype of African impoverishment, which Congolese filmmaker Neema calls out for still being “part of the extractive system.” She credits these “negative images” for proliferating low Congolese self-esteem. From this place of disempowerment, she says, it is “hard to project into the imaginary, and that makes you the best candidate for exploitation.” While systemic impoverishment may be a real issue Congolese people face, these one-dimensional narratives erase riches of the Congolese culture and environment and do not offer solutions or hope for the future of the Congo.

Centuries of overexploiting the DRC have created a massive discrepancy between the riches of Congolese land and the average quality of life of Congolese people. These issues of exploitation, disempowerment, and environmental degradation are what define the Congolese struggle for liberation: It is a pursuit of self-determination and sovereignty that is rooted in dignity, ancestral knowledge, environmental stewardship, and community.

What You Can Do for the Congo

Photo from Friends of the Congo.

Given its history of international involvement, it will take global attention and action in order for the situation in the DRC to improve. As Carney says, “The situation in the Congo is not just a Congolese issue, it’s not just an African issue. It’s a global issue, a worldwide issue…as a human being, at the very least, you ought to be concerned, you ought to say something, you ought to find out why this is happening, you ought to want to be moved to bring an end to it.”

If you’re interested in contributing to the Congolese fight for liberation, here are a few things you can do to help.

“With all these forces against the Congolese people, we’re making an appeal to people throughout the globe, to the masses, to come to the side of the Congolese.”

—Maurice Carney, Executive Director of the Friends of the Congo

For further reading, see Carney's recommended books below. Full reading list available here.

- White Malice by Susan Miller

- The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila: A People’s History by Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja

- The Assassination of Lumumba by Ludo De Witte

- The Lumumba Plot by Stuart A. Reid

- King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild

- King Leopold’s Soliloquy by Mark Twain

- Congo My Country by Patrice Lumumba

1 comment

This was an eye- opening article on The DRC. Thank you for your responsible reporting and advocacy.